Herbs are safe for kids! 4 rules every parent—and grandparent—needs to know

By Kerry Bone

I’ve been getting a lot of calls from concerned parents and grandparents lately, wondering if herbal remedies are safe for their little ones. It’s no wonder they’re worried, now that the most common over-the-counter cold and cough remedies have been pulled from the market amid serious safety concerns. Luckily, herbs are safe—even for children—as long as you follow a few specific rules.

Dosage: Getting it “just right”

One of the obvious issues is figuring out how much to give to a child—in other words, determining a safe dosage. There are lots of factors to consider here—especially the immature metabolism and digestion of children and infants. And given these difficulties, most experts agree that dosage guidelines for children are a bit of an imprecise affair. In fact, even a major pediatric medical textbook states that:

“Optimal tailoring of a drug’s [and herb’s] dose to the newborn infant and child is a delicate obligation of the treating physician… No universal dosage rule can be recommended.”

But even though there’s no single universal rule, there have been several different guidelines developed over the past few years. With that—and the need to be flexible and to use our judgment—in mind, let’s talk about how you can apply the safety standards that do exist for your own children or grandchildren.

Age-appropriate

Dosage rules are usually based on age, weight, or body surface area. While it’s probably the least familiar to you, most experts agree that body surface area is probably the most valid way to calculate dosage for children. The problem is, these sorts of calculations can be very complex. Which is likely why the earliest dosing rules simply used age as the basis for calculation. In fact, one of these age-based calculations, called Dilling’s rule, actually dates back to the 8th century. Dilling’s rule simply divides the child’s age by 20 to determine what fraction of the adult dose to administer. By today’s standards, though, Dilling’s rule is a bit outdated.

It’s been replaced by two other age-based rules, known as Young’s rule and Fried’s rule. Young’s rule involves taking the child’s age (in years) and dividing that number by the sum of the child’s age plus 12 (refer to the box on page 6 to see what Young’s rule looks like in mathematical terms).

Young’s rule is best for children between 2 and 12 years old. For infants, Fried’s rule is a better bet. Fried’s rule simply involves dividing the baby’s age (in months this time) by 150. The result is the fraction of the adult dose safe for the baby to take. Obviously the resulting dose will be quite low: For example, in the case of a one month old baby, only 1/150th of the adult dose would be given. The fact that Fried’s rule is so conservative is what makes it ideal for infants and toddlers up to about 2 years old.

Age-based rules are the simplest to calculate, but, despite the more complicated math, I always lean towards weight-based dosage rules as more relevant and useful for determining children’s doses of herbal remedies.

Size matters

The first of the weight-based rules, called Clark’s rule, was developed back in the 1930s. It involves dividing the child’s weight (in pounds) by 150. The resulting number is the fraction of the adult dose that should be administered to the child.

Again, like the age-based rules, Clark’s rule is easy to calculate, but, in my experience, it’s a bit oversimplified. I prefer another weight-based rule, one that is based on Clark’s rule. This one, called Augsberger’s rule, takes the child’s weight in kilograms (to determine kilograms, divide the weight in pounds by 2.2), multiplies it by 1.5, then adds 10. The result of this equation gives you the percentage of the adult dosage appropriate for the child. I know it sounds a bit complicated, but here’s an example that may help explain it a bit more.

Let’s say a child weighs 44 lbs. To determine his weight in kilograms, divide 44 by 2.2. This gives you a result of 20 kilograms. Now, to apply Augsberger’s rule, multiply the kilogram weight by 1.5. This equals 30. Then add 10 to that, giving you a total of 40. That final amount is the percentage of the adult dose that should be given to the child—in this case, 40 percent of the adult dose.

I mentioned above that, recently, most experts have come to agree that body surface area (BSA) is the best parameter to use in dosage calculations for children. Augsberger’s rule is actually a very good approximation of body surface area in children.2

But a group of anesthesiologists at Salisbury Hospital in England have come up with a simpler way to approximate BSA calculations.2 If the child’s weight is less than 30 kg, his or her weight is simply multiplied by 2 to determine the percentage of the full adult dose to administer. If the child weighs more than 30 kg, simply take his or her weight and add 30 to it to determine the correct percentage. So for a 20 kg child the dose is 40% (20 times 2) of the adult dose. And for a 35 kg child the dose is 65% (35 plus 30) of the adult dose.

Which rule fits best?

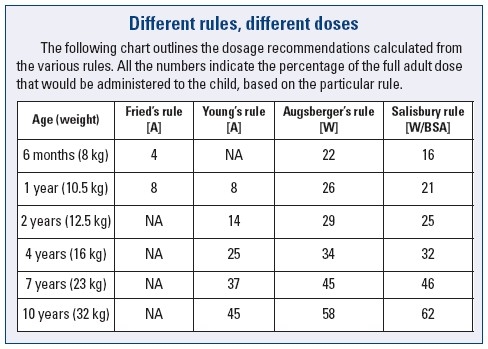

Again, I know all of this is probably more than a little confusing, so I put together a chart on page 7 that might help shed some light on things. The chart compares the percentages of the adult doses calculated using the different dosage rules. (Of course, the weights of different children vary for any given age, so for comparison purposes I used average weights.) For the Fried and Young rules, the “A” you see in brackets indicates that they’re based on age. For the Augsberger and Salisbury rules, the “W” indicates they’re based on weight (and the “BSA” added to the Salisbury rule indicates that it’s also an approximation of body surface area).

Take a look at the example of a 10-year-old child (average weight 32 kg). The Augsberger and Salisbury rules both indicate that around 60 percent of the adult dose is a good amount. Young’s rule only gives 45 percent, which is likely a bit too low. This is where the age-based rules start to break down: For older children they tend to lead to underdosing.

But looking at the chart example of a 6-month-old, there are some big differences. Young’s rule doesn’t even apply (it’s not used until a child reaches 1 or 2 years of age). Fried’s rule recommends 4% of the adult dose, Augsberger’s suggests 22%, and the Salisbury rule indicates 16%. The most accurate dose in this context is probably the 16% from the Salisbury rule, but keep in mind what we talked about earlier: infants have a very high degree of uncertainty because of their developing metabolisms. So even though it may not be as accurate, Fried’s rule is the best starting point for dosage in babies because it’s so conservative. The dose can always be adjusted upwards (to the Salisbury rule amount), if necessary, depending on the child’s response.

In general, I suggest Augsberger’s or the Salisbury rule for children 2 years old and up. For infants under 2 years, Fried’s rule should be used as the dosage starting point (especially when you’re using alcohol-based herbal extracts, such as tinctures). The dose can then be increased if necessary towards that predicted by the Salisbury rule. But I don’t recommend Augsberger’s rule for infants because it will very likely result in overdosing.

Winning the other half of the battle

Of course, finding the right dose is just one of the challenges in treating children. Delivery method can also present some problems. I’ve found that most kids can’t swallow tablets or capsules whole until they’re at least 9 or 10 years old. So that limits the options to liquid extracts, crushed tablets, or the powder contents emptied from capsules. Generally, none of them taste very good—and most children won’t willingly swallow things that don’t taste good!

But there are a few tricks you can use that will help, starting with mixing the herbal extract or supplement with some sort of natural sweetener. Some of the favorite “mixers” of my pint-sized patients include honey, all-natural fruit juice, juice concentrate, or pure maple syrup. Just add a dash of one of them to the extract or crushed supplement, and be sure to have more juice or water on hand as a “chaser.”

When all else fails, the “jello technique” is a good fallback. This involves mixing up a natural form of jello using fruit juice and agar powder (a natural gelling agent found in many natural food stores). Once the agar is dissolved into the juice, pour the mixture into the compartments of an ice cube tray, then add a single dose of the herbal extract to each cube. Put the tray into the refrigerator to set, and each time a dose is called for, give the child one jello cube.

For more information on using herbal treatments for young children, you may want to refer to the book I published last year on this topic (along with my colleague Rob Santich), titled Healthy Children: Optimising Children’s Health with Herbs. KB

| Following the rules Below are the mathematical equations for each rule. A=age, W=weight. (To convert lbs to kg, divide by 2.2) Young’s rule · A/(A+12) = the FRACTION of the adult dose · For a 4-year old child: 4/(4+12)= 4/16= 1/4 · The child would receive 1/4 the adult dose. (Multiply the adult dose by ¼ or .25) Fried’s rule · A in months/150 = the FRACTION of the adult dose · For an 8-month-old infant: 8/150 · The child would receive 8/150 of the adult dose. (Multiply the adult dose by 8/150 or .053) Augsberger’s rule · (1.5 x W in kilograms) + 10 = the PERCENTAGE of the adult dose · For a child weighing 25 kilograms: (1.5 x 25) + 10 = (37.5) + 10 = 47.5 · The child would receive 47.5% of the adult dose. (Multiply the adult dose by .475) Salisbury rule If weight is less than 30 kg, W in kilograms x 2 = the PERCENTAGE of the adult dose · For a child weighing 25 kilograms: 25 x 2 = 50 · The child would receive 50% of the adult dose. (Multiply the adult dose by .5) · If weight is more than 30 kg, W in kilograms + 30 = the PERCENTAGE of the adult dose · For a child weighing 45 kilograms: 45 + 30 = 75 The child would receive 75 percent of the adult dose. (Multiply the adult dose by .75) |